The park threatens to close. To stay open, Park West would need funding of 230,000 euros and government approval. The only problem: there is no government.

The park is part of a wider problem in Brussels. The city has been without a government for 560 days, and the problems pile on. The numbers don’t lie: shootings and drug-related crime have risen sharply in the past two years. It’s not what you would expect of an international hub with the EU and NATO residing in it.

The closing of the park is one of many consequences of this political deadlock, and it’s the reason why many local residents decided to come here today. The action is organised by Toestand, a local NGO that manages the park. But despite the rather sad reason behind the gathering, the vibe is jovial. A big tent hosts a local group serving volunteer-made food on a pay-it-forward basis. There are also multiple stands with activities, such as printing T-shirts, dancing, skating, and even forging on an anvil. Children play with chickens or ride around on a tandem bike, while a go-kart with a sound system attached drives around to make sure there’s music.

It’s a park that is home to many different local organisations and hobbyists.

At first sight, it’s not a very pretty park. It used to be an industrial site, and the city hasn’t transformed it into a real park yet. But NGO Toestand has tried to give it a temporary better look by adding structures and greenery.

It’s there that I meet Frederic Lamotte and his dog, Michelle. He’s a member of several local collectives and one of the founders of Respect.Brussels, a group that started last March to protest against the political standstill in Brussels. When asked about his involvement in so many collectives, he simply says: “It’s something I’ve done for years. It’s my role in the city.”

It becomes clear early in our conversation that he doesn’t have much love left for politicians. When I mention a certain Brussels politician, he lets out a cynical laugh and says, “What a klets.” He tells me they used to speak with politicians, and when I ask why they stopped, he answers simply: “Because they don’t listen.”

“We spoke with all the leaders, both Dutch-speaking and French-speaking. And everywhere we heard the same thing: “It's terrible. I've tried everything to unblock this. It's not my fault, it's the fault of the others.” And almost all of them say that.”

But how did Brussels get so stuck? Brussels is a bilingual city, and the government needs to represent both language communities. Each side must form its own majority before the two majorities can join into a single coalition agreement.

On the French-speaking side, a majority was quickly formed with MR, PS, and Les Engagés. On the Dutch-speaking side, things were more difficult. Shocking election results had made the completely new party TFA the second biggest, taking three of the 17 seats. Many parties immediately put a veto against TFA. To keep TFA out of the picture, they would have to form a four-party majority instead of the usual three. The problem was that there are only three ministerial posts, and each party in the majority wanted one. Eventually, after several months, they came up with a majority: Groen, Vooruit, N-VA, and Open VLD, with Open VLD losing out on a ministerial post.

However, the victory was short-lived. PS refused to work with N-VA in a coalition. Open VLD responded with its own veto, saying it would not join a coalition without N-VA. This blocked talks completely. On the Dutch-speaking side, forming another majority without N-VA and without Open VLD was close to impossible.

That leaves citizens facing very real consequences. Frederic explains how Brussels residents are affected: NGOs no longer receive subsidies, people susceptible to breast cancer cannot get screened, promised government support has not arrived, and drug users are pushed back onto the street as rehabilitation services have come to a standstill. He says politicians often forget these stories in their political game.

“When I heard the news, I just had to cry,” Frederic Lamotte says.

With all the vetoes in play, forming any majority or coalition is practically impossible. One party will eventually have to give up its veto, but for now that seems unlikely.

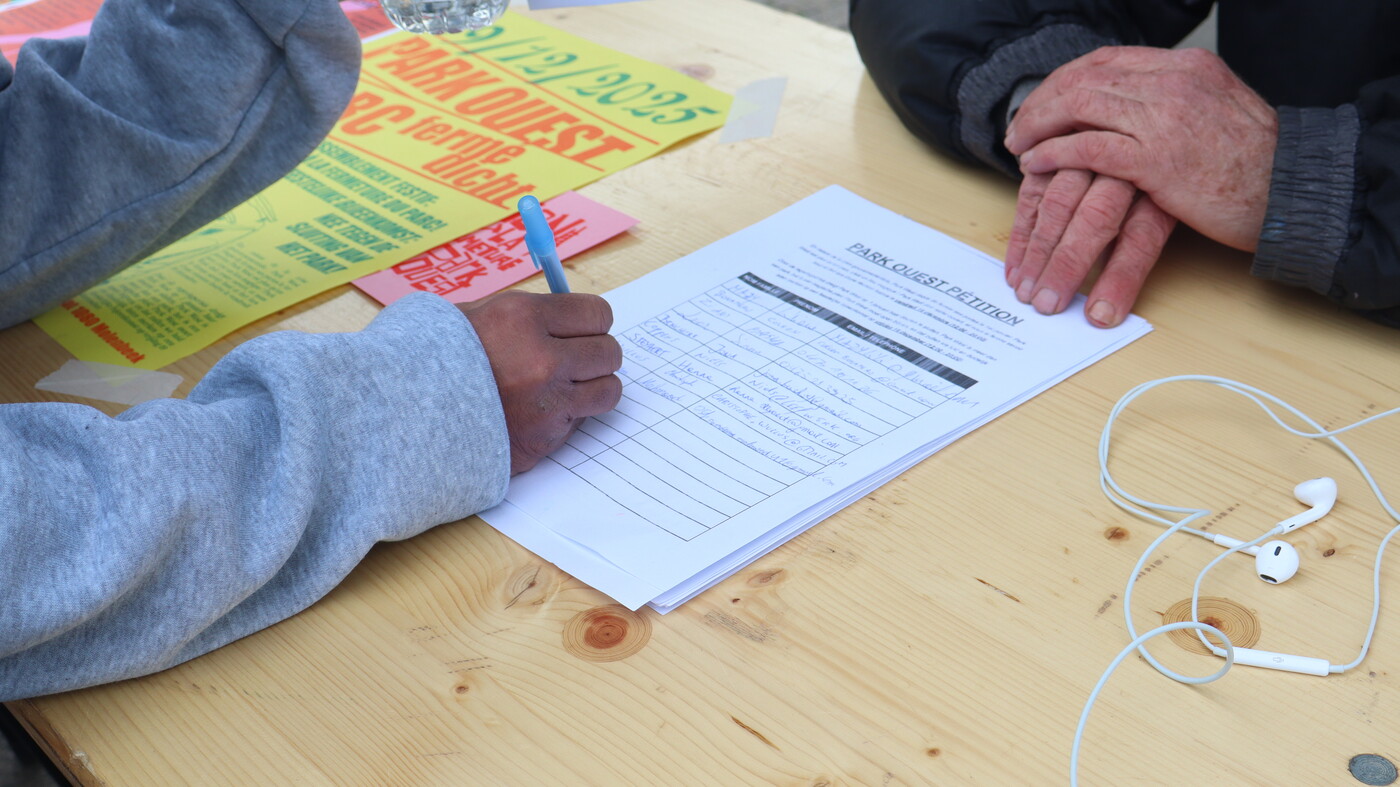

Old man at the entrance, gathering signatures for the petition.by Ella Pauwels

a fire next to the park's open signBy Ella Pauwels

Frederic lamotte with his dog MichelleBy Ella Pauwels

Children protesting with self-made signs against the political standstill in Brussels and the park's closure.By Ella Pauwels

Children biking on a tandem bike in the park.By Ella Pauwels

Go Kart with a sound system attached and a teens DJ-ing, with others enjoying the music.By Ella Pauwels

An aerial view of the parkby Ella Pauwels

Someone signing the petition.By Ella Pauwels

This park is one of many stories and is a much-needed public space for local residents. Between Ossegem and Zuidstation, almost all the squares have been taken over by drug dealers or closed by local authorities. This is one of the few places residents can still go in one of the most densely populated areas of Brussels.

A bit further we see children coming up, they’re chanting slogans and have made their own protest boards against the closing of the park and the political standstill. One of their boards read ‘fuck polictics, you’re making us sick’ wich rhymes in dutch. They’re from a local school, the klimpaal.

When I end my conversation with Frederic, I ask him if he still has hope. His answer surprises me: “Yes, I had lost hope. But after the conversation with Verhoegstraete (formateur), I thought okay they’re trying something new and there could be something to this. Because it's this or nothing. So yes, I think you're kind of obligated to keep hoping. Otherwise, I don't know what else to do.”

When I leave the park, I pass the old man again, he is still sitting alone but I can see that several pages of the petition are filled.