One of Isabella's books "Encyclopaedia of the Uncertain"(Adelė Pūkaitė)

As I come into Isabella’s apartment to record the interview, I notice a bunch of books laying on the carpet. ‘To Exist is to Resist’, ‘Encyclopedia of the Uncertain’, ‘What it takes to heal’ - I quickly scan the covers. Later as we talk, Isabella admits that she didn’t learn about patriarchy or feminism from the books: ‘Maybe I didn’t call that feminism yet, but it was clearly in my core. It was very much what my mom used to teach me, so in a strange way it was always a bit ambivalent. The interesting thing is, that she was always preaching about men and women equality, although at home she would behave differently.’

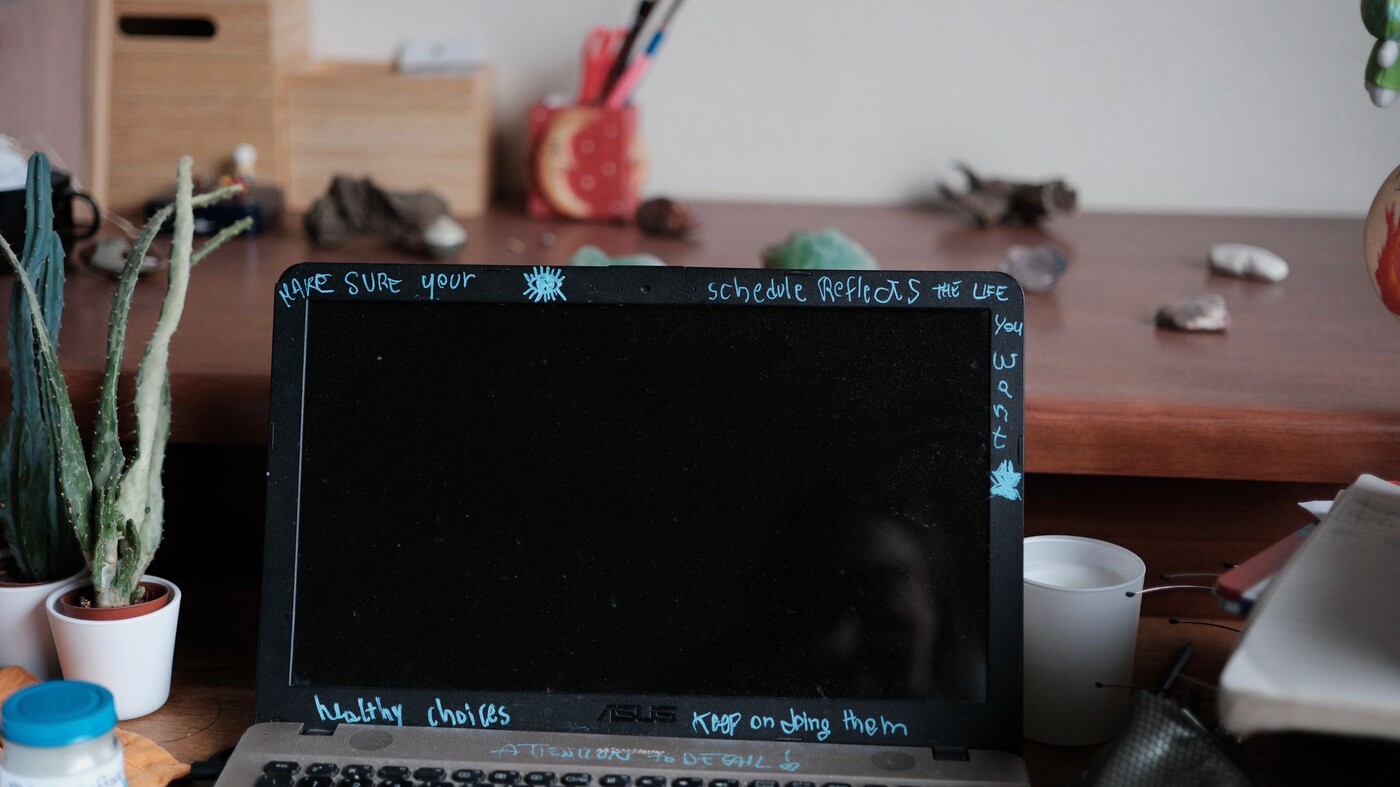

Isabella's computer(Adelė Pūkaitė)

Italian national identity traces its roots back to the Roman Empire. During the time, paterfamilias became the country’s standard, with the oldest male in a household effectively running and holding autocratic authority over family members. Isabella’s memories depict the common Italian family’s house rules: ‘Both of my parents worked, but my father wouldn’t cook, because ‘he’s already tired – it is expected that there is food made for him.’ And my mom, ridiculously enough, is coming home after him, and she would make food for us. Already seeing these little pieces of patriarchy in elementary school, I felt revolted by this.’

In Isabella’s mind, patriarchy is like a shadow that is bumping into you constantly. ‘Not bumping – smashing’, she corrects. ‘There is no way not to notice it. So I cannot not feel what, the way in which I'm considered, or treated, or and how that eventually diverts from how a male person is treated and felt.’

Isabella(Adelė Pūkaitė)

Part of why Isabella now lives in Belgium, are political reasons. And by that she means ‘the general mindset of society, the mainstream mindset’, which is ‘so far away from what is my mindset that I feel suffocated there’.

The related culture of machismo remained after the empire’s fall and continued with the Roman Catholic Church to the present day. Most Italians identify as Catholic, resulting in the church’s emphasis on patriarchal leadership and opposing women’s equality movements in the 20th century supporting view that women are inferior to men.

Male superiority is central to the newly introduced crime of femicide, the murder of a woman. I asked Isabella why she believes the term ‘femicide’ is important: ‘Femicide is explicitly a patriarchal crime. It's not like any woman that is killed, but specifically a woman that had been subjugated. In terms of power, the woman is put under a want of a man, specifically because she is a female.’

Isabella believes that femicide wouldn’t exist, if there was a gender – equal society. ‘We need to recognise that this crime stems from a fundamental power imbalance, a predominance of power on one side, because without this disparity, the crime simply would not happen.’

Although Isabella agrees that the bill is a step to the right direction, she assesses it critically: ‘‘That's great base on which you can always work on, and you can for sure, always built on it, but… It seems hypocritical. I’m afraid the current government is trying to keep the society happy for a second, like ‘here, take this, and be quiet. Especially when you consider that just a week after the law was passed and highly praised by the society, the Italian Parliament stalled a different law about effective sexual education in schools, meanwhile comprehensive sex education is vital, in my opinion. It’s important to challenge gender norms and address gender-based violence.

Isabella in front of her window(Adelė Pūkaitė)

Whilst officially making femicide a crime is great base on which we can always work on, and built on, Isabella doesn’t see herself living in Italy. According to her, such a diminishing view of a woman is too big of a part of the textile of the society in Italy, that ‘you can feel it on your skin when you're on the street’. And the biggest problem of all might be the fact that the major society tends to diminish or downplay it, - ‘You know, I am an immigrant in Belgium. Xenophobia is quite obvious to me. I know it, I notice it. And still, experiencing xenophobia is somehow easier to endure than patriarchy back home.

Since xenophobia or racism are broadly shamed upon, the majority of society acknowledge it and condemn it. Meanwhile patriarchism in Italy is a brushed off topic. In Isabella’s experience that makes it harder to live with: ‘Many Italians say that ‘it’s not as bad as depicted’, ‘it’s not that common’, so they don’t only question it, but also do not believe in it. In the extent of it, in the harm of it. It’s a negation to myself, if I go back there.’